Iranians bemoan sanctions hardship as vote approaches

21:18 - 6 February 2012

Each day that he struggles to buy food for his family, vegetable seller Hasan Sharafi shoulders part of the burden of Iran\'s defiance of the West over its nuclear programme. He can hardly bear it.

\"Prices are going up every day, life is expensive. I buy chicken or meat once per month. I used to buy it twice per week,\" the father of four said in Iran\'s central city of Isfahan.

\"Sometimes I want to kill myself. I feel desperate. I do not earn enough to feed my children.\"

With just a month to go before a parliamentary election, Iran has been hit hard in recent months by new U.S. and European economic sanctions over its nuclear programme, which Tehran says is peaceful but the West says is aimed at making a bomb.

In conversations in towns and cities across Iran, people complained of rapidly deteriorating economic conditions, likely to be the main issue in an election that exposes divisions between President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and hardline opponents.

The last time Iranians voted, in a 2009 presidential election, Ahmadinejad\'s disputed victory triggered eight months of violent street demonstrations. The authorities successfully put down that uprising by force, but since then the Arab Spring has demonstrated the vulnerability of governments in the region to uprisings fuelled by anger over economic difficulty.

\"My father lost his job because the factory he used to work for 30 years was closed last month. I am so pessimistic. Why is this happening to us?\" lamented mathematics student Behnaz in the northern city of Rasht.

\"I don\'t know whether the prices are rising because of sanctions. The only thing that I know is that our lives are ruined. I have no hope for the future.\"

Iran\'s leaders deny that sanctions are having an economic impact, but are also calling for solidarity in the face of them. In a defiant speech on Friday, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei told Iranians sanctions would make them stronger.

\"Such sanctions will benefit us. They will make us more self reliant,\" he said in a televised address marking the anniversary of Iran\'s 1979 revolution. \"Sanctions will not have any impact on our determination to continue our nuclear course.\"

BREAD ON THE TABLE

Such rhetoric resonates with some Iranians, who say they are willing to endure pain to defend a nuclear programme that has become a symbol of national pride.

\"America uses the nuclear issue as an excuse to replace our regime with a puppet regime to control our energy resources. But we will not let them. Nuclear technology is our right and I fully support our leaders\' view. Death to America,\" said student Mohammad Reza Khorrami in the northern town of Chalous.

But the West is hoping sanctions will turn ordinary Iranians against their leaders, and there are clear signs of discontent. When you ask Iranians about the nuclear issue, many seem to see it as a distraction from the real question of economic hardship.

\"I am not a politician. I don\'t care about the nuclear dispute. Soon, I might not be able to afford food and other basic needs of my children,\" said Mitra Zarrabi, a schoolteacher and mother of three.

\"What is the nuclear dispute? Don\'t waste my time asking irrelevant questions,\" said 62-year-old peddler Reza Zohrabi in a marketplace overflowing with imported Chinese goods in the city of Kashan. \"I\'m not interested in talking about politics and the nuclear issue. I have to find ways to put bread on my family\'s table.\"

Iranian authorities say 15 percent of the country\'s workforce is unemployed. Many formal jobs pay a pittance, meaning the true figure of people without adequate work to support themselves is probably far higher.

Hemmat Ghorban, 32, sits in a square in Mashhad city with a group of men, waiting to get work as day construction workers.

\"I used to sell fruit in a small shop in Zanjan city,\" said Ghorban, who was forced to close his shop because of the increasing rent and high price of materials.

\"Today I earned nothing. How am I going to support my family? Soon my family will be homeless. Sometimes I go without work for three or four days.\"

The new sanctions include measures signed into law by President Barack Obama on New Year\'s Eve that would ban any institution dealing with Iran\'s central bank from the U.S. financial system.

If fully implemented, the law would effectively make it impossible for countries to pay for Iranian oil. Washington is imposing the sanctions gradually and offering waivers to prevent chaos on international energy markets, but countries seeking those permits are expected to reduce trade with Iran over time.

The European Union, which collectively bought about a fifth of Iran\'s 2.6 million barrels per day of oil exports last year, has announced it will halt Iranian crude imports. Other countries are scrambling to comply with U.S. and EU measures.

Since the sanctions have only begun to bite, far greater pain is looming. Oil is 60 percent of Iran\'s economy. Much of its food and animal feed are imported, and many of its factories assemble goods from imported parts.

Already, ships bringing grain have been turning back from Iranian ports because Tehran cannot pay suppliers: an agricultural consultancy said maize imports from Ukraine - a major source of animal feed - fell 40 percent last month.

China, Iran\'s biggest trade partner, cut its purchases of Iranian oil by half in January and February this year, and is seeking steeper discounts for the oil that it does buy. Turkey wants a discounted price for gas.

Such discounts mean that even if it does manage to thwart sanctions and find buyers for its energy exports, Iran\'s revenue will be hurt. It relies on oil exports to buy goods to feed its 74 million people and pay for subsidies to keep prices low.

People have been queuing at banks to withdraw their savings and buy hard currency, even though banks have increased interest rates on savings to 20 percent from 12 percent.

Currency exchange shops are refusing to sell dollars at official rates, forcing people to the black market where the rial has lost more than half its value in the past two months.

For those who link the hardship to international sanctions, the most vivid example is neighboring Iraq, where an embargo imposed between 1991 and the U.S. invasion in 2003 reduced a wealthy oil exporting country to dire poverty.

\"I don\'t want Iran to become like Iraq before America\'s invasion. With the sanctions, soon we will have problems finding essential goods and even medicine,\" said 31-year-old teacher Rokhsareh Sharafoleslam in Chalous.

Reformist candidates are largely barred from standing in Iran\'s parliamentary election, which will put Ahmadinejad - known in the West as a hardliner - against opponents that are even more conservative. The election will largely be a referendum on Ahmadinejad\'s economic policies, which his opponents blame for the economic disarray.

For decades, Iran has used its oil wealth to provide the public with lavish subsidies for goods. Ahmadinejad has been cutting those subsidies, replacing them with direct payments to citizens of around $110 a month for a family of four.

His hardline political opponents say the payments are a bribe to win support from voters and have fueled inflation.

Analyst Hamid Farahvashian said the payments could nevertheless win voter support for the president.

\"The lower-income people in villages and small towns can live on that money. So, Ahmadinejad\'s camp basically will win their votes in parliamentary polls.\"

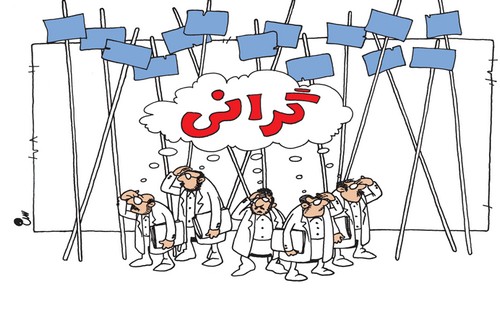

INFLATION, UNEMPLOYMENT

Iran\'s annual official inflation rate is running around 20 percent but economists and some lawmakers say it is really around 50 percent. Prices for bread, dairy, rice, vegetables and cooking fuel have soared. A traditional Iranian loaf of \"sangak\" bread costs 30 percent more than a few months ago.

\"We are worried and afraid. I feel depressed when I think about future of my children. What might happen if America and other countries impose further sanctions on Iran?\" said a housewife in Kermanshah, who declined to give her name.

Reza Khaleghi, who owns a small grocery store in the central city of Karaj near Tehran, said gloomily: \"Because of sanctions prices are increasing almost every day. The purchasing power of people is nose-diving.\"

Since 2010, subsidy cutbacks have tripled the price of electricity, water and natural gas used for factories, cooking and heating homes. Soaring costs caused the closure of at least 1,800 small factories in Tehran province alone, according to Iranian media.

On a bus from Mashhad to the nearby town of Quchan, people spoke of little else but inflation.

\"Prices are increasing by the hour. My husband and I cannot afford starting a family as life is so expensive,\" said Mahla Aref, a government employee.

Small businesses say they are struggling to operate as the falling currency raises the cost of goods.

\"Business is almost dead. People only buy essential basics,\" said Khosro Sadegi, who plans to shut down his electronics and appliance shop in the town of Sari.

\"Because of rial fluctuations we have to increase prices and people just don\'t buy anything anymore.\"

Source - Reuters

\"Prices are going up every day, life is expensive. I buy chicken or meat once per month. I used to buy it twice per week,\" the father of four said in Iran\'s central city of Isfahan.

\"Sometimes I want to kill myself. I feel desperate. I do not earn enough to feed my children.\"

With just a month to go before a parliamentary election, Iran has been hit hard in recent months by new U.S. and European economic sanctions over its nuclear programme, which Tehran says is peaceful but the West says is aimed at making a bomb.

In conversations in towns and cities across Iran, people complained of rapidly deteriorating economic conditions, likely to be the main issue in an election that exposes divisions between President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and hardline opponents.

The last time Iranians voted, in a 2009 presidential election, Ahmadinejad\'s disputed victory triggered eight months of violent street demonstrations. The authorities successfully put down that uprising by force, but since then the Arab Spring has demonstrated the vulnerability of governments in the region to uprisings fuelled by anger over economic difficulty.

\"My father lost his job because the factory he used to work for 30 years was closed last month. I am so pessimistic. Why is this happening to us?\" lamented mathematics student Behnaz in the northern city of Rasht.

\"I don\'t know whether the prices are rising because of sanctions. The only thing that I know is that our lives are ruined. I have no hope for the future.\"

Iran\'s leaders deny that sanctions are having an economic impact, but are also calling for solidarity in the face of them. In a defiant speech on Friday, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei told Iranians sanctions would make them stronger.

\"Such sanctions will benefit us. They will make us more self reliant,\" he said in a televised address marking the anniversary of Iran\'s 1979 revolution. \"Sanctions will not have any impact on our determination to continue our nuclear course.\"

BREAD ON THE TABLE

Such rhetoric resonates with some Iranians, who say they are willing to endure pain to defend a nuclear programme that has become a symbol of national pride.

\"America uses the nuclear issue as an excuse to replace our regime with a puppet regime to control our energy resources. But we will not let them. Nuclear technology is our right and I fully support our leaders\' view. Death to America,\" said student Mohammad Reza Khorrami in the northern town of Chalous.

But the West is hoping sanctions will turn ordinary Iranians against their leaders, and there are clear signs of discontent. When you ask Iranians about the nuclear issue, many seem to see it as a distraction from the real question of economic hardship.

\"I am not a politician. I don\'t care about the nuclear dispute. Soon, I might not be able to afford food and other basic needs of my children,\" said Mitra Zarrabi, a schoolteacher and mother of three.

\"What is the nuclear dispute? Don\'t waste my time asking irrelevant questions,\" said 62-year-old peddler Reza Zohrabi in a marketplace overflowing with imported Chinese goods in the city of Kashan. \"I\'m not interested in talking about politics and the nuclear issue. I have to find ways to put bread on my family\'s table.\"

Iranian authorities say 15 percent of the country\'s workforce is unemployed. Many formal jobs pay a pittance, meaning the true figure of people without adequate work to support themselves is probably far higher.

Hemmat Ghorban, 32, sits in a square in Mashhad city with a group of men, waiting to get work as day construction workers.

\"I used to sell fruit in a small shop in Zanjan city,\" said Ghorban, who was forced to close his shop because of the increasing rent and high price of materials.

\"Today I earned nothing. How am I going to support my family? Soon my family will be homeless. Sometimes I go without work for three or four days.\"

The new sanctions include measures signed into law by President Barack Obama on New Year\'s Eve that would ban any institution dealing with Iran\'s central bank from the U.S. financial system.

If fully implemented, the law would effectively make it impossible for countries to pay for Iranian oil. Washington is imposing the sanctions gradually and offering waivers to prevent chaos on international energy markets, but countries seeking those permits are expected to reduce trade with Iran over time.

The European Union, which collectively bought about a fifth of Iran\'s 2.6 million barrels per day of oil exports last year, has announced it will halt Iranian crude imports. Other countries are scrambling to comply with U.S. and EU measures.

Since the sanctions have only begun to bite, far greater pain is looming. Oil is 60 percent of Iran\'s economy. Much of its food and animal feed are imported, and many of its factories assemble goods from imported parts.

Already, ships bringing grain have been turning back from Iranian ports because Tehran cannot pay suppliers: an agricultural consultancy said maize imports from Ukraine - a major source of animal feed - fell 40 percent last month.

China, Iran\'s biggest trade partner, cut its purchases of Iranian oil by half in January and February this year, and is seeking steeper discounts for the oil that it does buy. Turkey wants a discounted price for gas.

Such discounts mean that even if it does manage to thwart sanctions and find buyers for its energy exports, Iran\'s revenue will be hurt. It relies on oil exports to buy goods to feed its 74 million people and pay for subsidies to keep prices low.

People have been queuing at banks to withdraw their savings and buy hard currency, even though banks have increased interest rates on savings to 20 percent from 12 percent.

Currency exchange shops are refusing to sell dollars at official rates, forcing people to the black market where the rial has lost more than half its value in the past two months.

For those who link the hardship to international sanctions, the most vivid example is neighboring Iraq, where an embargo imposed between 1991 and the U.S. invasion in 2003 reduced a wealthy oil exporting country to dire poverty.

\"I don\'t want Iran to become like Iraq before America\'s invasion. With the sanctions, soon we will have problems finding essential goods and even medicine,\" said 31-year-old teacher Rokhsareh Sharafoleslam in Chalous.

Reformist candidates are largely barred from standing in Iran\'s parliamentary election, which will put Ahmadinejad - known in the West as a hardliner - against opponents that are even more conservative. The election will largely be a referendum on Ahmadinejad\'s economic policies, which his opponents blame for the economic disarray.

For decades, Iran has used its oil wealth to provide the public with lavish subsidies for goods. Ahmadinejad has been cutting those subsidies, replacing them with direct payments to citizens of around $110 a month for a family of four.

His hardline political opponents say the payments are a bribe to win support from voters and have fueled inflation.

Analyst Hamid Farahvashian said the payments could nevertheless win voter support for the president.

\"The lower-income people in villages and small towns can live on that money. So, Ahmadinejad\'s camp basically will win their votes in parliamentary polls.\"

INFLATION, UNEMPLOYMENT

Iran\'s annual official inflation rate is running around 20 percent but economists and some lawmakers say it is really around 50 percent. Prices for bread, dairy, rice, vegetables and cooking fuel have soared. A traditional Iranian loaf of \"sangak\" bread costs 30 percent more than a few months ago.

\"We are worried and afraid. I feel depressed when I think about future of my children. What might happen if America and other countries impose further sanctions on Iran?\" said a housewife in Kermanshah, who declined to give her name.

Reza Khaleghi, who owns a small grocery store in the central city of Karaj near Tehran, said gloomily: \"Because of sanctions prices are increasing almost every day. The purchasing power of people is nose-diving.\"

Since 2010, subsidy cutbacks have tripled the price of electricity, water and natural gas used for factories, cooking and heating homes. Soaring costs caused the closure of at least 1,800 small factories in Tehran province alone, according to Iranian media.

On a bus from Mashhad to the nearby town of Quchan, people spoke of little else but inflation.

\"Prices are increasing by the hour. My husband and I cannot afford starting a family as life is so expensive,\" said Mahla Aref, a government employee.

Small businesses say they are struggling to operate as the falling currency raises the cost of goods.

\"Business is almost dead. People only buy essential basics,\" said Khosro Sadegi, who plans to shut down his electronics and appliance shop in the town of Sari.

\"Because of rial fluctuations we have to increase prices and people just don\'t buy anything anymore.\"

Source - Reuters