Femicide: The Murder of Soraya Alimohammadi by Her Husband with a History of Addiction, Domestic Violence, and Family Pressure

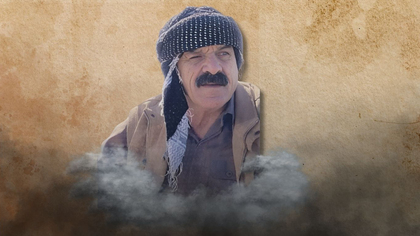

On Tuesday, September 2, 2025, Soraya Alimohammadi, a 35-year-old woman living in Baharestan neighborhood of Saqqez, who had endured years of domestic violence, severe marital conflict, and her husband’s addiction to methamphetamine (“shisheh”), was attacked during a quarrel by her 40-year-old husband, Afshin Sharifi. He stabbed her multiple times and then doused her with gasoline in the parking garage of their home, setting her on fire. She later died from her injuries.

According to a source speaking to Kurdpa, Soraya Alimohammadi had long been a victim of domestic abuse, her husband’s drug addiction, and repeated family disputes. Two days before her murder, she had left her husband’s home because of these conflicts and returned to her parents’ house. However, under difficult circumstances and pressure from her father, she was forced to return to her husband’s home.

On the day of the murder, after a heated argument, Afshin Sharifi stabbed Soraya several times in the neck and body, leaving her unconscious. He then tied her hands and feet, dragged her half-alive body to the garage, poured gasoline on her, and set her on fire.

Neighbors, alerted by smoke and her screams, rushed her to a medical facility, but she succumbed to severe burn injuries.

Afshin Sharifi, a resident of the village of Kahrizeh in Saqqez County, was arrested by police less than an hour after the crime. He had a record of severe drug addiction and violent behavior within the family.

Soraya Alimohammadi and Afshin Sharifi had one child together.

Human Rights Context and Lack of Protection for Women in Iran

The murder of Soraya Alimohammadi occurred in a context of legal gaps, systemic neglect, and impunity for perpetrators of domestic violence. Despite the rising cases of femicide, the Islamic Republic of Iran still lacks a comprehensive law prohibiting violence against women. A draft bill on the subject has been stalled for years, and its protective provisions have been significantly weakened.

In Iran’s penal code, some provisions — such as Article 630 of the Islamic Penal Code — effectively allow men under certain circumstances to kill their wives. In many cases, domestic violence is either not criminalized or treated with judicial leniency. Victims are often left without shelters, legal protection, or access to effective psychological and legal services.

Iran has also not acceded to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and has performed poorly in implementing its existing international obligations.

Murders such as Soraya’s are a direct result of the government’s failure to protect women and its reinforcement of a culture of impunity. Without legal reform, public education, and stronger protective mechanisms, violence against women will persist.

Femicide and Suicide in Kurdistan: Structural Discrimination, Social Exclusion, and a Security-Oriented State Approach

According to Ovin Mostafazadeh, spokesperson for Kurdpa, femicide and suicide in Kurdistan are deeply intertwined with socio-economic and political conditions. By marginalizing and keeping Kurdistan underdeveloped, the government deprives people of opportunities and social mobility, leaving individuals without the education and awareness necessary to address social harm and crises.

At the same time, the state, through its security-oriented approach to Kurdistan, attempts to portray social harms as inherent to Kurdish culture, while in fact, culture is fluid — and in other countries, significant budgets are allocated to its development.

This does not mean denying harmful traditions within Kurdish society. Indeed, in recent years, women’s rights activists and gender equality advocates, often with minimal resources, have played a leading role in challenging femicide and suicide, raising awareness, and resisting patriarchal traditions. Many have been arrested, and women’s associations have been shut down or denied license renewals.

Human rights activists, media, and organizations have not hidden or denied cases of femicide and suicide. On the contrary, they have sought to raise public awareness and turn these social harms into a collective concern.

Importantly, victims of femicide and suicide are not passive: in recent years, many of the women who have taken their own lives or been killed lost their lives in the course of resisting traditions and discrimination.

This report aims to highlight the complexity of social harms in Kurdistan and the structural entanglements behind them, as any one-dimensional reading of the issue is deeply misleading.