Government crime against a Bukan family during Jin, Jiyan, Azadi: mother shot, father forcibly disappeared.

The Mameh and Abdolghaderi family from Bukan were among those subjected to some of the most brutal state repression during the Jin, Jiyan, Azadi uprising. Over a 52-day period, Shahin Abdolghaderi, the mother, was shot in the head with 300 pellets; her son, Ardalan Mameh, was struck by over 20 pellets; and the father, Osman Mameh, became a victim of enforced disappearance. For more than two and a half years since the protests began, this family has endured ongoing systemic human rights violations — including the denial of legal recourse, lack of medical treatment, absence of accountability, and official concealment of the crime. Due to continuous pressure and threats from security forces, they were ultimately forced to flee the country in order to seek medical care for the mother and pursue international justice for the father’s disappearance.

In this report, Kurdpa presents a detailed and documented account of the government’s systematic abuse against the Abdolghaderi-Mameh family, based on an in-depth interview with Ardalan Mameh. His testimony outlines the sustained repression they have faced for more than two and a half years following the Jin, Jiyan, Azadi protests.

1. October 2022: IRGC’s Rampant Crackdown on Kurds in Iran and Iraq — The Night 300 Pellets Were Fired at Shahin Abdolghaderi's Head

On October 6, 2022 — the twelfth night of nationwide protests sparked by the state killing of Jina (Mahsa) Amini — security forces intensified their violent crackdown in Kurdish cities including Divandarreh, Dehgolan, Saqqez, Urmia, Piranshahr, Qasr-e Shirin, Kermanshah, Oshnavieh, Ilam, Eslamabad-e Gharb, Sonqor, Quchan, and Kangavar, resulting in the deaths of 25 Kurdish civilians.

That night marked a new phase in the government’s repression: the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) launched a dual-front assault — both inside Iran and across the border in Iraqi Kurdistan. In the morning, the IRGC fired missiles at bases belonging to Kurdish opposition parties in Iraqi Kurdistan, killing 17 people. Simultaneously, in cities across Iranian Kurdistan, IRGC forces conducted sweeping and indiscriminate crackdowns on protesters in streets and public spaces.

Among the victims was Shahin Abdolghaderi, a 54-year-old woman from Bukan. That night, she was shot in the head from less than a meter away with 300 pellets. More than two and a half years later, many of these pellets remain embedded in her skull due to the state's deliberate denial of medical treatment.

2. The IRGC’s Blind and Terrorizing Crackdown Inside Kurdish Cities — Ardalan Mameh Recalls the Night 300 Pellets Were Fired at His Mother

“That night, my grandmother was in critical condition,” says Ardalan Mameh. “Our family got in the car to visit her. Around 9:30 p.m., we reached Salmandan Street at the intersection of Madar Square. The traffic was heavy, and we were stuck, waiting for it to clear. Cars were honking repeatedly — a form of protest at the time. Security forces, stationed at the square — which also hosts a local IRGC base — were already deployed.”

He describes the scene: IRGC forces in camouflage combat uniforms with black masks over their faces, many carrying shotguns — the primary weapon used during the early protests. Later, they would switch to Kalashnikovs and even heavy machine guns like DShKs.

“We were in our car — I was driving, and my mother sat behind me. They had already begun firing at cars, regardless of whether drivers were honking. They didn’t give warnings or check vehicles — just shot at them, smashing windows and beating the cars with their rifle butts.”

When IRGC forces reached their vehicle, over 20 officers surrounded them. First, they shot twice at the windshield and frame. The initial shots missed the family. Then, they fired into the back of the car. A shell struck Shahin Abdolghaderi in the head from less than a meter away, tearing off part of her left ear and embedding plastic pellet shells in her head — where many remain to this day. Ardalan was also hit, sustaining around 20 pellets to his head.

“At the time, going to a hospital wasn’t an option,” he explains. “Seeking treatment meant being charged — whether it was one pellet or a hundred.”

As chaos spread, drivers tried to flee. Ardalan says that in the two minutes they remained in the area, he saw more than six vehicles ahead of and behind them targeted in the same indiscriminate manner. “That night marked both the beginning of the mass protests and a new level of state violence. IRGC forces fired blindly, without checking who was in the cars or whether they were injured. They had one order — to shoot. Nothing else mattered to them.”

3. Deliberate Denial of Medical Care by the State — Bukani Hospital Used as a Tool of Repression and Intimidation

Ardalan Mameh recounts the harrowing night he tried to get his wounded mother medical help — and instead faced an extension of the regime’s crackdown inside the very place meant to heal.

Bukān has only one hospital: Shahid Gholipour, a crumbling, outdated facility that “resembled a clinic more than a real hospital.” When the family arrived there with Shahin Abdolghaderi — her head riddled with shotgun pellets — they were immediately met by state security agents present on the premises.

Because of the growing protests and the government’s escalating violence, hospitals had effectively been turned into tools of fear and enforcement. Medical staff throughout Kurdistan had been threatened and warned not to treat wounded civilians.

“As soon as we entered,” Ardalan says, “a man in plain clothes approached us — obviously a government agent. He carried a notepad and began interrogating us: ‘Why are you injured? Where were you shot? Who shot you?’ My father responded: ‘You’ve filled the streets with armed men shooting at civilians without warning. My wife is dying.’ The man just said ‘It was a mistake’ and walked away to question other patients.”

Every injured person who entered the hospital was interrogated. Young people were detained. Older adults were dismissed as mistaken casualties. The environment was overwhelmingly hostile — even doctors and nurses were under threat.

The only care Shahin received that night was having two sterile gauze pads placed on her wounds. “They told us a specialist needed to see her — but none came. Repeated calls went unanswered. Specialists, likely terrified under pressure, refused to respond. Normally they’d be summoned from home, but this time they just said they weren’t available.”

Even pharmacies had been threatened. “We couldn’t get basic supplies — saline, sutures, local anesthetics. We didn’t even know what medications she needed because no one would tell us.”

This section reveals how the health care system was not only collapsed under pressure — it had been weaponized. Wounded civilians were denied care not by accident, but by design.

Treatment Under Threat and Scarcity — Ear Reconstruction Without Pellet Removal, and Continued Interrogation in Saqqez Hospital

The day after the shooting, the family tried once again to have Shahin Abdolghaderi admitted to Gholipour Hospital in Bukan, but they were turned away once more. Through a friend, they managed to find a doctor in the nearby city of Saqqez. That afternoon, they traveled there.

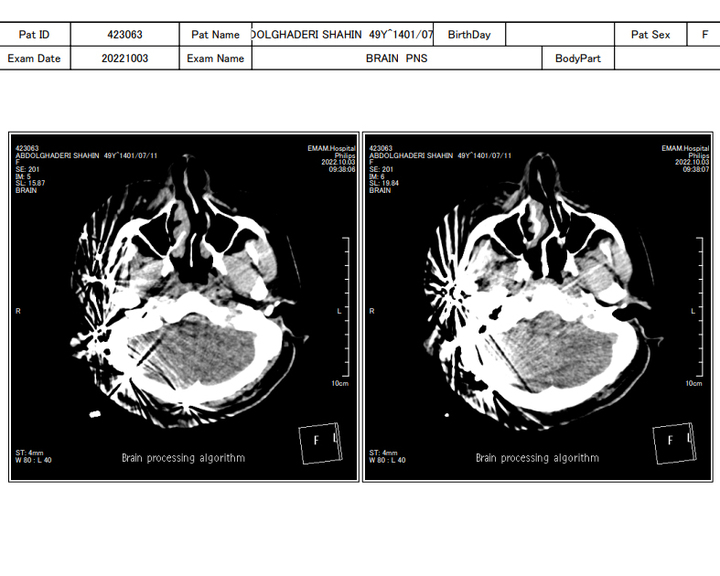

The doctor examined Shahin in his private clinic and agreed — at his own risk — to take responsibility for her treatment. He then arranged for her to be admitted to Imam Khomeini Hospital in Saqqez. Due to a lack of proper medical equipment, the pellets lodged in her skull could not be removed. The most they could do was reconstruct her ear and prescribe antibiotics to prevent infection. (One of the photos reportedly shows her face visibly swollen from the infection.)

Shahin remained hospitalized for two days. During that time, doctors managed to perform the ear surgery and partially contain the infection with medication. However, hospital staff warned the family they should not stay any longer. Even in Saqqez, the environment was intensely securitized. Throughout the day, plainclothes agents entered the hospital at regular intervals — every 30 to 60 minutes — carrying a notepad and questioning the injured: “You’re the one who’s been wounded? Where? How?”

Despite having a death certificate for their grandmother and CT scans and records from the hospital in Bukan, the family was not safe. The pressure, surveillance, and atmosphere of fear extended into every room — even those intended for healing.

This passage underscores the fact that access to medical care, even where it technically existed, came under severe intimidation and risk — for patients, families, and even the physicians who dared to help.

Denial of Responsibility and Abandonment of Suffering — A Medical Committee in Tehran Yields No Results Due to Lack of Resources

Doctors at the hospital in Saqqez advised the family to seek further evaluation in Tehran, suggesting a medical committee might determine whether it was possible to surgically remove the pellets embedded in Shahin Abdolghaderi’s skull. The family submitted CT scans and medical images and, through their own persistent efforts, managed to get a committee convened.

The committee concluded that due to limited resources — and more critically, because the pellets had lodged in nerve-dense areas — surgery was too risky. There was a serious chance of causing permanent facial paralysis. Additionally, as is standard in Iran, any surgical procedure requires a signed waiver stating that the patient and family assume full responsibility for any complications. The family was told: “If anything goes wrong during surgery, the liability is yours.”

As a result, despite spending a month organizing this process, no surgery was performed.

During that month, Shahin was cared for at home using only the medications and ointments prescribed by the doctor in Saqqez. Her wounds were disinfected with Betadine, and ointment was applied to her ear. This was essentially home care, not physician-supervised treatment. The medical committee never followed up, as all the coordination had been informal and initiated by the family — not through any institutional or governmental channel.

Summons, Threats, and Forced Commitment by IRGC Intelligence in Saqqez to Silence the Case of Shahin Abdolghaderi's Injuries — A Complaint that Went Unanswered

Ardalan Mameh recounts that during the month following the incident, the Intelligence branch of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) in Saqqez repeatedly contacted his family. They called every phone number they could find, eventually coercing the family to respond. They were told: “You have to come in. If you don’t, we’ll come and take you ourselves.” Once there, the family was forced to sign a written pledge stating that “no photos must be published, nothing must be said, and any disclosure about this incident will have consequences for you.”

According to Ardalan, what they experienced during that period was not an investigation, not a legal process, not even a basic administrative procedure — it was nothing but the imposition of silence through threats and coercion.

Despite this, the family still tried to pursue the matter through official channels. They submitted a formal written complaint to the very same IRGC Intelligence office in Saqqez, stating that none of their family members had participated in the protests, and that their sole request was to be allowed to secure medical treatment for Shahin.

However, this complaint led nowhere. No case was opened, no answer was provided, and not even a follow-up phone call was made. In essence, they were met with a wall of denial, indifference, and intimidation — and absolute silence.

Over Two and a Half Years Later: Chronic Infections, Severe Headaches, Facial Paralysis, and Sleepless Nights — The Lingering Consequences of That Night for My Mother

In the time since that night, my mother has suffered from four to five severe infections, each time forcing us to rely on antibiotics such as cephalexin, amoxicillin, and others to manage the condition — because no other medical options were available. Today, she continues to live with serious and lasting physical complications: intense and frequent headaches, especially at night; complete numbness in her cheeks and the left side of her face; muscle drooping on that side; and a persistent and debilitating sleep disorder.

Most nights, she is unable to sleep at all. With every change in weather, the pain and infections worsen. Her daily life remains fundamentally and painfully shaped by the trauma of that night.

4. November 18, 2022 — The Night the Regime Called the “Cleansing of Bukan”: Ardalan Mameh’s Account of His Father’s Enforced Disappearance

On the night of November 18, 2022, Bukan was under heavy security lockdown. The protests had reached their peak, and Bukan had become one of the epicenters of both mass mobilization and brutal repression. That night, government forces shot and killed two protesters, Shahriar Mohammadi and Milad Maroufi.

According to Ardalan Mameh, it was also the night when the bodies of Hiva Janjan, Shahriar Mohammadi, and Milad Maroufi were buried. The authorities later dubbed it the "Night of Bukan's Cleansing." The commander of the IRGC, along with other regime officials, held a ceremony to commemorate this “cleansing” and declared that Bukan had been “secured.” Following that night, the intensity of protests in Bukan temporarily decreased.

Large numbers of suppression forces were brought in from surrounding towns, and the city descended into chaos. Ardalan’s father, Osman Mameh, was alone that night. No one saw him. Surveillance cameras around the city had been redirected skyward by protesters to prevent identification. As a result, there is no footage of him. That was the night he never came home.

On November 18, 2022, Osman Mameh — the father of the family — was subjected to an enforced disappearance.

The Enforced Disappearance of Osman Mameh: From a Disconnected Phone to Official Silence and Unofficial Hints of Arrest

That night, Osman Mameh was at his brother’s home. Between midnight and 1 a.m., he set out alone from the Aliabad neighborhood of Bukan—located in the city center—heading home. The area is full of narrow alleyways, and to reach the main street and get to a car, he had to walk through several of them. It was on this route that Osman was arrested and forcibly disappeared.

Around 12:30 a.m., he called me and said, “I’m on my way home.” We said goodbye. Just seconds later, I tried to call him again to tell him not to come back—the city was in chaos—but his phone had already been turned off and was out of reach. From that moment until the day we were forced to flee Iran, we kept trying to contact him, but the phone remained off, unreachable.

That night, due to the complete disorder and heavy security presence in the city, we were unable to take any action. The next morning, we visited the criminal investigation unit, hospitals, and other relevant institutions, but found no trace of him. The first day passed without answers. On the second day, we were advised to file a missing person report. A lawyer we spoke with encouraged us to formally declare him missing, explaining that doing so would make it more difficult for the authorities to hide his whereabouts.

At the police department, they told us: “If he’s not in the custody of plainclothes or intelligence forces—if he’s just lost or left the country—we’ll inform you within 24 hours. But if he’s been detained by the military, we’re neither responsible nor able to help.” And that’s exactly what happened. It’s now been over two and a half years, and we have received no news.

My father was alone. No one saw him at that moment. Surveillance cameras at protest sites had been pointed toward the sky by demonstrators to avoid facial recognition, so even the footage revealed nothing.

Later, we were told—unofficially—that he had been arrested. This information came not from official sources or documents, but through individuals close to the regime (known locally as Jash in Kurdistan). We paid these individuals a significant amount of money to obtain even a hint of my father’s fate. The names of those people and what they said are all carefully documented and in our possession.

To pursue any leads, we spent everything we had. We owned only one house, which we sold, using the entire sum to chase down information about my father’s disappearance.

Over 15 Summonses, Beatings, and Death Threats by Bukan’s Intelligence Office: Ardalan Mameh on the Cost of Speaking Out About His Father’s Enforced Disappearance

Inside Iran, I repeatedly brought public attention to my father's disappearance. Each time the issue was covered by the media, I was summoned by the Intelligence Office in Bukan. The first two times, I was interrogated verbally. But in subsequent visits, the situation escalated into violence. I was beaten. The security agents accused me of being the source of the information shared with the media. I denied it, but the pressure only intensified. One officer from the Bukan Intelligence Office told me explicitly, “If you insist on pursuing your father’s case and speaking about it, it’s no trouble for us — we’ll make you disappear just like him.”

The Bukan Intelligence Office was the only agency that contacted us regarding my father's case. Even after we officially filed a missing person complaint — which, by law, should have been followed up by the criminal investigation department — no institution other than that intelligence office responded. They were the only ones calling us, threatening us, and summoning me. If I didn’t answer their calls, they would start contacting other family members until one of us complied.

Whenever I was summoned to the intelligence office, my phone was immediately confiscated at the entrance. The building had PVC doors and tiny, sealed interrogation rooms — about two meters by one — with a desk and one chair for the interrogator and another for the detainee. The doors and windows could only be opened from the outside.

While I was still in Iran, I was summoned to that office approximately 15 times. The number of threatening phone calls I received was so high, I eventually stopped counting.

Continued Threats, Surveillance, and Psychological Torture: From Repeated Summonses to Bans on Public Participation

We had a government-affiliated individual living in our neighborhood—someone from the IRGC—who was also keeping us under surveillance. On multiple occasions, I received phone calls from security agents telling me things like: “Go wait with your car at such-and-such location. A vehicle will arrive, and it will drop off some wounded and detained people, including your father. Take him home.” This same scenario was repeated more than ten times. I waited late at night at the spots they mentioned—but no vehicle ever came.

Around the anniversary of the protests—or whenever a strike or public demonstration was expected—they would call us again, warning us not to leave our home or participate in any public activity. They said that if we did, we would face serious consequences, and it would come back to haunt us.

5. Forced Departure from Iran Under Threat, Psychological Torture, Medical Dead-Ends, and Silence on Enforced Disappearance

In addition to repeated summonses, direct threats, and heavy surveillance, we endured another form of torment—ongoing and crushing psychological pressure. Individuals affiliated with government and IRGC institutions frequently approached me and blatantly said things like, “Your father was executed in such-and-such a place,” or “He was killed on this date.” Then they would add, “Pay us some money, and we’ll bring you his clothes and shoes.”

These security lies and psychological games were repeated countless times, each time with a new story or scenario—but always with the same goal: to destroy hope, humiliate us, and crush any attempt at seeking the truth. Eventually, we reached a breaking point. With no real path to justice, and while my father’s fate remained locked away, my mother’s physical and mental health sharply deteriorated. Her condition worsened daily, and we had no viable options for her treatment inside Iran.

Faced with this reality, we made the decision to leave Iran. But even this path was blocked. Because of constant surveillance by security forces, we were not able to leave the country legally. In the end, we had no choice but to escape the country illegally, crossing dangerous borders to seek safety.

6. Family Collapse in the Shadow of Enforced Disappearance and State Violence: Living Through the Aftermath of a Crime

They shattered our family. They destroyed its foundation. My father was forcibly disappeared, my mother nearly killed by shotgun pellets, and I—their son—sacrificed my youth and my efforts in a path of survival and justice for the crime inflicted upon us.

Psychologically, we’ve faced severe trauma. The constant pressure has deeply affected every member of our family. My father was a seasonal construction worker—an ordinary citizen. Each time we approached legal or security authorities, we explained that he had no political affiliation, no organizational ties. Even his work records as a simple laborer were available and showed no justification for his arrest or disappearance.

I, Ardalan, 29 years old, with a master's degree in mechanical engineering, owned a small garage in Iran and worked in car restoration. I had a life. A profession. But I had to leave it all behind and flee the country. We are men, and we're always expected to endure and stay silent. But the truth is, I’m not okay. I honestly don’t know how to explain what we’ve been through. The only thing that matters to me now is to help my mother heal—and to be the voice of my father.

I ask all international human rights organizations to pursue my father's case. Perhaps at least one victim of enforced disappearance can be found.

Compiled by: Awin Mostafazaded